A short introduction to XState

Welcome my son, welcome to the machine - Pink Floyd

Everything that’s interactive needs some state. All apps have state, web pages with forms, SPAs, and so on. As the app grows, so does the state. At some point, it becomes hard to manage.

Most of the time, a bad state might not be a big issue. But sometimes it can be fatal. A decade ago, Toyota had a huge problem because of bad state. Toyota cars suffered from sudden “unintended acceleration”, that is the car was still accelerating even if you didn’t press the gas pedal, and even if you pressed the brake. People were dying because of this.

Long story short, the problem was in the firmware. It used global variables for the state. Among those global variables, was one keeping track of acceleration. When that flag was true, the car was deemed to accelerate. And it did. The only issue was that the process that was supposed to reset the flag sometimes failed. So the flag stayed true and the car was accelerating even if was not supposed to.

So it’s pretty obvious that in some cases at least, we need solid state management. One of the solutions is a finite state machine (FSM):

It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The FSM can change from one state to another in response to some inputs; the change from one state to another is called a transition - Wikipedia

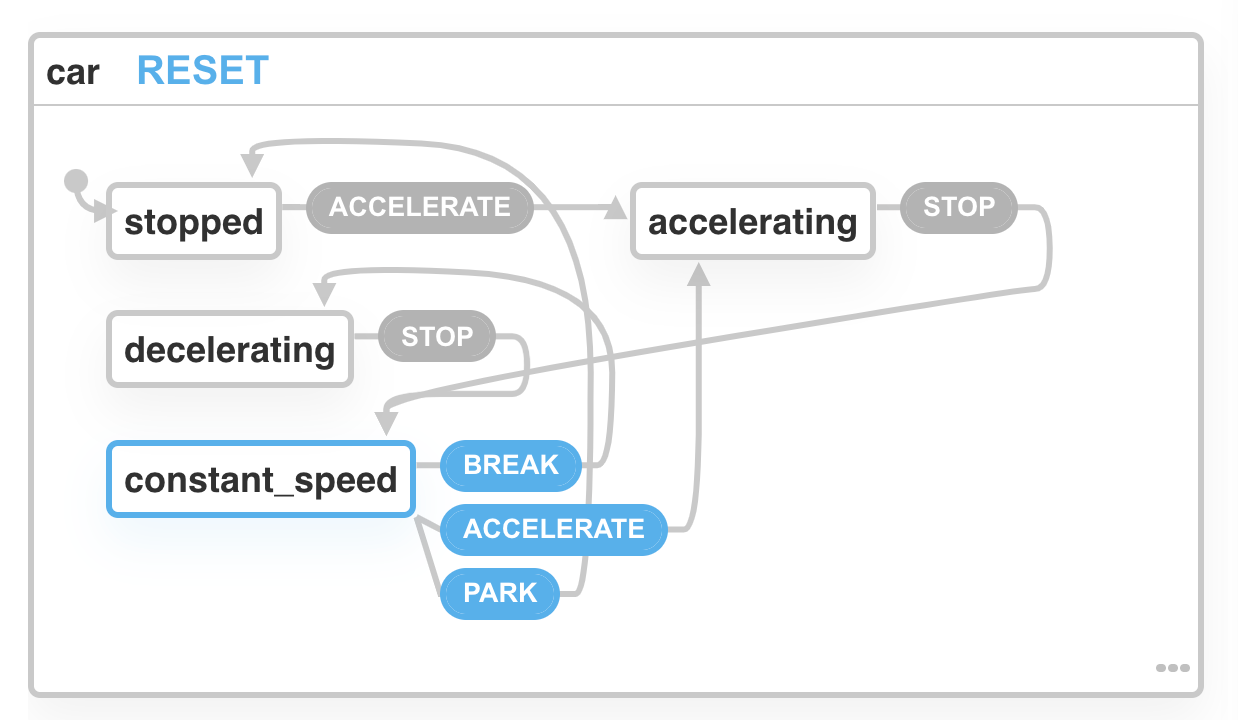

If we were to model a finite state machine for a car, among the possible states is “accelerating” and “decelerating”, but the machine can be only in one of the states at a time, not both.

This means that:

- The car can be stopped, accelerating (increase speed), decelerating(decrease speed), or can have a constant speed.

- To start the car or to increase the speed you need to accelerate. The moment you take your foot off the gas pedal, the car stops accelerating.

- To decrease the speed you need to decelerate. The moment you take your foot off the brake pedal, the car stops decelerating.

- When the car is not accelerating or decelerating the speed is constant (even if is stopped)

An implementation of the FSM using XState looks like this:

const carMachine = Machine({

id: "car",

initial: "stopped",

states: {

stopped: {

on: {

ACCELERATE: "accelerating",

},

},

accelerating: {

on: {

STOP: "constant_speed",

},

},

decelerating: {

on: {

STOP: "constant_speed",

},

},

constant_speed: {

on: {

brake: "decelerating",

ACCELERATE: "accelerating",

PARK: "stopped",

},

},

},

});

The initial state is “stopped”, then we set the possible states (that must include the initial state.) Each state accepts at least one event (all caps labels), which are used to go from one state to another.

You can copy the above code inside XState Visualizer and play with it.

XState

XState is a finite state machine implementation in JavaScript. It can be used with vanilla JavaScript, React, Vue, and other JavaScript frameworks.

First, you need to add the xstate npm package to your project:

npm install xstate --save

Then import Machine or createMachine where you create the machine:

import { Machine, createMachine } from "xstate";

Machine and createMachine have the same effect, but Machine will be deprecated in the future, so you should use createMachine.

However, createMachine is not available today on XState Visualizer so we’re forced to use Machine there.

There are two things we need to know:

- How to configure the machine to work as we want

- How to use the machine: how to read and change state

Configuration

To create a machine, we need to provide a configuration (which is a simple JavaScript object). The configuration needs two things :

- the initial state

- the available states (which must contain the initial state)

The simplest machine can have only one state. If we ignore the time before the Big Bang, the universe is always expanding. A machine for the universe looks like this then:

const config = {

initial: "expanding",

states: {

expanding: {},

},

};

const universeMachine = Machine(config);

If machines have more than one state, we need ways to make the machine change state. These ways are called events. Unless one of these events occurs, the machine will maintain the same state.

We cannot just send any random events, we need to trigger events that are understood by the machine and more precisely, events that are available for the current state.

Consider the following lightbulb machine. A light bulb can either be lit or unlit.

const config = {

initial: "unlit",

states: {

lit: {},

unlit: {},

},

};

const lightbulbMachine = Machine(config);

We can turn on the bulb when is unlit, and turn it off when is lit. This means that the LIT event is available only when the light bulb is unlit, and the UNLIT event is available only when the bulb is lit.

const config = {

initial: "unlit",

states: {

lit: {

on: {

UNLIT: "unlit",

},

},

unlit: {

on: {

LIT: "lit",

},

},

},

};

const lightbulbMachine = Machine(config);

The events supported by a state are set inside an on object, set as a state object property. By convention, the names of the events are in full caps.

If you send events that are not supported by the current state, they are ignored!

The value for an event is the targeted state that the machine should transition to. As a shorthand, we can just specify the name of the state, but that is the same as the following:

const config = {

initial: "unlit",

states: {

lit: {

on: {

UNLIT: {

target: "unlit",

},

},

},

unlit: {

on: {

LIT: {

target: "lit",

},

},

},

},

};

const lightbulbMachine = Machine(config);

So now the question is why should I use the long version instead of the shorthand? Because the long version allows you to also set some actions that are executed when the event is triggered:

const config = {

initial: "unlit",

states: {

lit: {

on: {

UNLIT: {

target: "unlit",

actions: [() => console.log("Hello darkness my old friend...")],

},

},

},

unlit: {

on: {

LIT: {

target: "lit",

actions: [() => console.log("Let there be light...")],

},

},

},

},

};

const lightbulbMachine = Machine(config);

Now you might think that This machine looks useful but I need some of my state somewhere. I can see how I can use a machine with an API call but where am I suppose to keep the API response data? The answer is the machine’s context!

A third thing you can configure for a machine, after state and events, is the context: the data you want to keep in the machine.

To keep things simple, let’s continue with the light bulb machine and assume the light bulb is intelligent: it’s guaranteed to be turned on and off 10000 times. When it approaches that limit, it sends an email to notify you to buy a new one.

const mailService = {

send: (msg) => {

console.log(msg);

},

};

const config = {

initial: "unlit",

context: {

limit: 0,

},

states: {

lit: {

entry: (context, event) => {

if (context.limit > 9900 && context.limit % 10 === 0) {

// approaching limit

mailService.send("Please buy a new smart light bulb!");

}

},

on: {

UNLIT: "unlit",

},

},

unlit: {

on: {

LIT: {

target: "lit",

actions: assign({ limit: (context, event) => context.limit + 1 }),

},

},

},

},

};

const lightbulbMachine = Machine(config);

How this works:

- With have an initial context with the limit state set to 0

- Each time we send a LIT event we use assign action to increase the limit

- When the limit is over 9900 and limit is multiple of 10 and we enter lit state, we use the email service to send an email

Of course, there are many more ways to configure a machine. Read the XState documentation to find the configuration that suits you.

Usage

We can use the machine in two ways: read its state and send events to change the state.

Before we can use the machine we need to use an interpreter to create an instance of the machine. This means we can have multiple machine instances, each with its own state. That makes sense right? We have multiple light bulbs in our house and we cannot use the same machine for all because some might be on and some off.

import { interpret } from 'xstate'

...

const lightbulbMachine = Machine(config);

// create machine instance

const service = interpret(lightbulbMachine).start();

// to get the machine state

const currentState = service.state.value;

// to see if it matches a state

const isLit = state.matches('lit'));

// to read context

const { limit } = state.context;

// we can also use the service to send events to the machine

const nextState = service.send('LIT');

The way this is supposed to work is to create the machine instance somewhere and send it in all the code that needs the machine.